Just the facts ma’am. Dragnet sergeant Joe Friday was famous for cutting to the facts, which is exactly what we intend here in this, our first post exclusively for Guitarist. So grab your favorite axe, here we go.

The most important three facts regarding the guitar fingerboard:

1 Repetition

2 Repetition

3 Repetition

Did I mention the guitar was repetitious? The key to mastering the guitar fingerboard is to harness its repetitious nature to work in your favor.

Assuming a 24 fret guitar (most have 22, or 21 – but many have 24), check out these facts:

- 24 frets = 4 octaves

- 4 octaves = 48 different notes

- Each string = two full octaves

- 24 frets times 6 strings = 144 positions!

- The note E3 can be played in six different positions! (most instruments only have one position per note)

- 10 notes are repeated in 5 positions

- 10 notes are repeated in 4 positions

- 10 notes are repeated in 3 positions

- 10 notes are repeated in 2 positions

- 10 notes are played in 1 position

Did you catch that – only 10 notes are played in one position. The rest are repeated in multiple positions, with an average of three positions per note!

Advantage: notes, intervals, scales, arpeggios, and chords can all be easily played chromatically up and down the neck using the same fingering. Another words, switching keys is a simple task for guitarist.

Disadvantage: Since most notes are duplicated in multiple positions, the guitarist is faced with constant left-hand position choices – making it a more difficult instrument to sight-read on than most other instruments.

The interval between each string on the guitar are Perfect 4ths (P4). Starting from low E, we count 4 alpha names and arrive at A, the next string on the guitar:

1 2 3 4

E F G A 1/2 1 1 = P4 - 2.5 steps

Actually, 4 string basses continue this series of P4 between each string. However, the interval between the 3rd and 2nd string on the guitar is a major 3rd:

1 2 3

G A B

1 1 = ma3 - 2 steps

After that, the guitar resumes with a P4 interval between the 2nd and 1st strings.

If it weren’t for the major 3rd interval between the 3rd and 2nd strings, the guitar would be perfectly symmetrical – all perfect 4ths. If that were the case, repetitious patterns would become much more obvious and simpler, and in fact there are numerous guitarist who’ve decided to tune their guitars that way for this very reason:

6 5 4 3 2 1

E A D G B E = Standard tuning

E A D G C F = P4 symmetrical tuning

The obvious disadvantage of doing this is you isolate yourself from the rest of the music / guitar world – all chord charts and tablature would be unusable.

The best of both worlds is to harness and optimize on the nearly symmetrical nature of the guitar, while still playing in standard tuning. That is the approach the majority of professional guitarist employ, self included.

The chart below takes the guitar fingerboard and lays it out linearly – like a piano keyboard – from the lowest note to the highest. By doing this, we get a clear view of the repetitious nature of the guitar fingerboard:

| Note | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| E1 | 0 | |||||

| F1 | 1 | |||||

| F#/Gb1 | 2 | |||||

| G1 | 3 | |||||

| G#/Ab1 | 4 | |||||

| A1 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| A#/Bb1 | 6 | 1 | ||||

| B1 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| C1 | 8 | 3 | ||||

| C#/Db1 | 9 | 4 | ||||

| D1 | 10 | 5 | 0 | |||

| D#/Eb1 | 11 | 6 | 1 | |||

| E2 | 12 | 7 | 2 | |||

| F2 | 13 | 8 | 3 | |||

| F#/Gb2 | 14 | 9 | 4 | |||

| G2 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 | ||

| G#/Ab2 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 1 | ||

| A2 | 17 | 12 | 7 | 2 | ||

| A#/Bb2 | 18 | 13 | 8 | 3 | ||

| B2 | 19 | 14 | 9 | 4 | 0 | |

| C2 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 1 | |

| C#/Db2 | 21 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 2 | |

| D2 | 22 | 17 | 12 | 7 | 3 | |

| D#/Eb2 | 23 | 18 | 13 | 8 | 4 | |

| E3 | 24 | 19 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 0 |

| F3 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 6 | 1 | |

| F#/Gb3 | 21 | 16 | 11 | 7 | 2 | |

| G3 | 22 | 17 | 12 | 8 | 3 | |

| G#/Ab3 | 23 | 18 | 13 | 9 | 4 | |

| A3 | 24 | 19 | 14 | 10 | 5 | |

| A#/Bb3 | 20 | 15 | 11 | 6 | ||

| B3 | 21 | 16 | 12 | 7 | ||

| C3 | 22 | 17 | 13 | 8 | ||

| C#/Db3 | 23 | 18 | 14 | 9 | ||

| D3 | 24 | 19 | 15 | 10 | ||

| D#/Eb3 | 20 | 16 | 11 | |||

| E4 | 21 | 17 | 12 | |||

| F4 | 22 | 18 | 13 | |||

| F#/Gb4 | 23 | 19 | 14 | |||

| G4 | 24 | 20 | 15 | |||

| G#/Ab4 | 21 | 16 | ||||

| A4 | 22 | 17 | ||||

| A#/Bb4 | 23 | 18 | ||||

| B4 | 24 | 19 | ||||

| C4 | 20 | |||||

| C#/Db4 | 21 | |||||

| D4 | 22 | |||||

| D#/Eb4 | 23 | |||||

| E5 | 24 |

There are really only two fingerings on the guitar. What? Are you crazy! Probably. However, after pain staking study of this repetitious nature of the guitar fingerboard – with the goal of revealing a simpler way to view it – studying every method for learning fingerings for chords, scales, modes, arpeggios – it finally became obvious that there is a much simpler way of viewing and harnessing this monster into submission. In fact, it is so simple, yet so misunderstood and never discussed, I may have to kill you after revealing it (not).

This concept applies to every element in music. To keep things simple and clear, we will start with one of the most basic musical components: the triad arpeggio. Arpeggios are simply broken up chords. They are in fact chords, that are performed by playing each note individually, instead of strumming or plucking. You can arpeggiate a chord by picking out the notes from bottom to top, top to bottom, or any pattern you can think up.

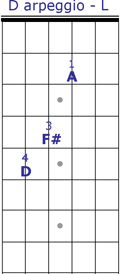

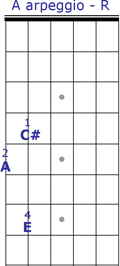

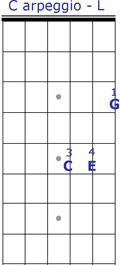

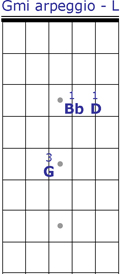

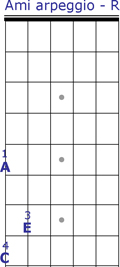

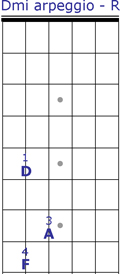

First, let’s look at an A arpeggio beginning on the low 6th string, and compare it to a D arpeggio on the adjacent 5th string. The patterns are more important than the alpha names – since as you will see these patterns repeat themselves all over the neck:

Notice the pattern and fingerings for these two chords are identical. Also, this triad arpeggio pattern could be played anywhere on the neck. This particular fingering pattern falls on the Left side of the root.

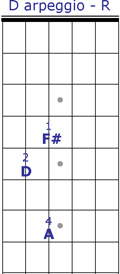

Now let’s take a look at a different pattern:

Here the fingering pattern falls on the right side of the root. That’s it – those are your two fingerings – everything is either on the Left side of the root, or the Right side. There are only two sides to a coin – in this case, the fingerboard is the coin.

As you will see, this dual fingering pattern concept applies to every element in music on the guitar.

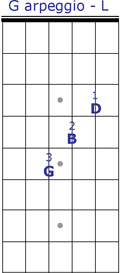

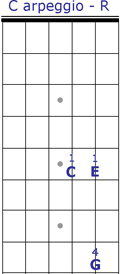

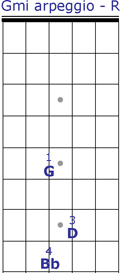

Let’s continue moving across the fingerboard and see what happens next:

Aha! These patterns look different – what gives? Relax – remember our discussion regarding the guitar being “almost” symmetrical – requiring us to mentally adjust for the 3rd to 2nd string? The D note on the G chord would be one fret lower, if the interval distance between strings remained constant – and would have produced the exact fingering pattern as above. So, in reality, these are the same fingering patterns when you make the mental adjustment.

Take a look at the C arpeggio and mentally adjust both the E and G back one fret, and it also produces the same pattern. Fact is, these are identical voicings – but are “masked” by the asymmetrical tuning of the guitar. We just need to practice removing the mask!

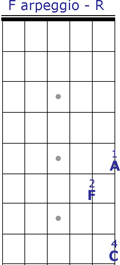

Let’s take a look at the Right side fingering counterparts:

Both the G and F patterns are identical, even matching the A and D patterns above.

The C pattern, which involves the 3rd and 2nd string, requires mentally sliding both the E and G back – just as we did with the Left-side pattern above, revealing it too is the same right-side pattern as the others.

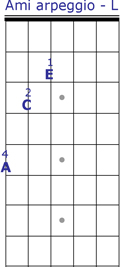

Now let’s take a look at the minor triads for these chords, starting with Left side fingering positions:

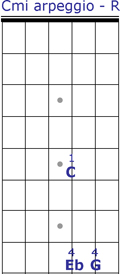

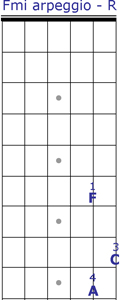

Once again we have identical fingering patterns. The next two are also identical, once we mentally adjust the D back on the Gmi chord, and both the Eb and G back on the Cmi chord:

The right-side Ami, Dmi, Gmi, and Fmi are all identical fingerings, while the Cmi arpeggio requires mentally sliding the G note back one fret – then, as you can see, these are all identical Right side fingerings.

In summary, we’ve been discovering the repetitious nature of the guitar fingerboard. Other than the G to B string, the guitar is tuned in perfect fourths, giving it a beautiful symmetrical platform which inspires musical creativity. Keep practicing making the one-fret mental shifts back where appropriate, and soon the symmetrical, repetitious quality of this great instrument will come alive before your very eyes and ears!

We’ll continue our exploration of the guitar fingerboard, extending into chords and scales in our next blog. Until then I remain,

Musically yours,

Al

Recent Comments